Quirkat Studios: Staying True to Arab Culture

This is not just a story about electronic gaming. Nor is it about Quirkat, the Jordanian studio billed with creating the important strategy game Arabian Lords. This story is about the ongoing daily struggle that bright Arab entrepreneurs and innovators wage to educate investors about the potential of their niche markets. Ultimately, the story is about relevance to Arab culture when investing. It’s about creating original products in a region that is losing its unique cultural identity as innovators to becoming franchisers of everything from Starbucks to Fox Movies and the Louvre.

By Bilal Hijjawi

The last decade of mega investment in the Arab region can aptly be labeled as being brick-headed. Many billions of petrodollars poured into brick and mortar to invent all kinds of ostentatious property. On the other side of the investment spectrum, productive technology sectors were left thirsting for proper funding. Many new and brilliant technology projects and novel ideas will now have to wait for another round of aggressive investing; one that finds value in productive sectors.

According to the founders of Amman-based electronic games developer Quirkat, Mahmoud Khasawneh, and Jordanian British Candide Kirk, finding investors that can relate to niche technology businesses or ideas is a modern-day “Jihad” in the Arab region.

“The investment ecosystem in other markets pushes ideas and has an established logical structure. In the US for example, you sleep in a sleeping bag, drink water and coffee and use your core skills to create something that others will notice; and when they notice they come in with their teams to move your business to the next level. Here you do all your battles; you create the product, then staff the firm, do all the taxes and manage the team, then fight very skilled businessmen to attract their investment,” says Khasawneh, who handles the business aspects of Quirkat.

The duo, however, has been luckier than most Jordanian entrepreneurs. They’ve been exposed to global markets and have taken their battles outside the Arab region to find the right investor. They managed to sell their electronic strategy game idea to BreakAway, a leading US-based game developer, after Arab investors shunned them.

The result was a title that cost over $5 million to develop and launch.

Most Jordanians can’t go outside for funding, says Khasawneh. “How do you expect young Jordanian entrepreneurs in their early 20s to create a brilliant product, sell it to Arab businessmen, negotiating terms successfully so that they’re not screwed? They can’t.” In the US, it isn't unusual that 20-year old college students create the biggest brands for cyber and IT out of a garage; consider the now mega brands Microsoft, Apple, Google, Facebook and Twitter.

Most of the Arab investors that Quirkat’s founders met advised them to follow the cheaper way of licensing and Arabizing games from international sources. “But we’ve set out to become a content specialized company; we have the skills for authoring games not copying them” says Kirk. “We can’t remain commission agents, franchisees, Arabizers of foreign content; we need original content,” she continues.

Worldwide, electronic games are big and vital industries. After all, they make up a large part of the powerful cyber and social trends globally. United States President Barrack Obama recently named a $2-million Digital Media and Learning Competition Prize as part of his initiative to improve education in math and science nationally. Two leading universities, Sony, Electronic Arts and national IT associations are also lending support to the Prize, as they have done with any popular game development that introduces science and math-related levels or adventures.

With Quirkat, the founders took a risky detour in their careers that only few other Jordanians would consider. They launched their game studio after quitting well-paid senior posts at the Ministry of Communication and Technology (MOICT), where they worked to implement Jordan’s e-Government initiative.

When Khasawneh approached Kirk about establishing a studio for developing original, complex and animated strategy games for Arabs, she thought it was a great but impossible dream. Kirk, herself a dedicated gamer, was well aware that electronic games required high talent, were resource-intensive and cost a lot of money. Arab markets didn’t have any competitive game studios for that reason and most games were copies and Arabized international game titles. The market for products based on Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) is also riddled with problems because piracy is ubiquitous in Arab software markets.

Nevertheless, the two would set up this ambitious enterprise in 2005, and Arabian Lords, a multiplayer strategy game, was to be created. The game, developed in the span of one year, revolved around the Islamic Empire of the 13th Century and its trade routes. “It’s a blend of real-time strategy that lets players take the role of an enterprising merchant lord as they start with one palace and expand to rule an ancient empire,” says Khasawneh.

Their goal, adds Kirk, was to create an inspirational strategy game that would appeal to Middle East gamers while offering historical accuracy and cultural relevance. In December 2006, Arabian Lords was ready for marketing and distribution.

“We had two virtual teams working across different continents to develop the game,” says Khasawneh. A Jordanian team of nine employees worked on developing the game’s story themes while BreakAway handled the complex technical issues. Quirkat outsourced research to local history teachers to remain true to the historic period and hired professional Jordanian actors to do the voiceovers and the logistics to turn this dream project into reality.

“Our relation with the BreakAway required a lot of trust-building in the early stage and we won that eventually. Our partner was eventually quite impressed as we delivered our part ahead of schedule. We’re very proud that we were credited alongside a famous international brand name as joint developers,” says Khasawneh.

While Quirkat had surmounted the challenges of creating an original and potentially commercially viable game, it still faced many hurdles. The first came from regional distributors. "It took us eight months of convincing and negotiations to get the product on the shelves of the big chain distribution channels," he says adds. They faced a hard sell because regional distributors weren’t convinced the game would generate demand.

Expatriates who didn’t speak Arabic managed most of the big regional distribution chains and they had not yet come across a single Arab production that promised to sell as well as foreign game titles. “Arabian Lords was the first big Arab game that the distributors had seen. That’s why it took months of convincing them that it was worth their shelf space,” he adds.

To their surprise, Arabian Lords immediately proved an instant success, filling a client niche many distributors hadn’t even known existed. After the market responded quite positively to the new product, Virgin Megastores would dedicate a whole section for the game across the region.

Saudi Arabia, their most promising market, however, blocked the sale of Arabian Lords under the pretext that the word “entertainment” was inappropriate when used to label content inspired by Islamic history. This, however, didn’t stop the country’s dedicated gamers from ordering their copies via online stores. Quirkat still managed to ship 4,000 copies through on- line channels. “The beauty of e-commerce is that you can always bypass physical borders,” comments Kirk.

“From the numerous online forum discussions and blogs, we could tell that our networked strategy game was a hit among Arab gamers everywhere,” adds Khasawneh. Quirkat ingeniously priced its game to render piracy much less attractive. Their pricing of the product varied according to the purchase power of each export market. The price for the Levant market for example was $15, making the original product a more attractive alternative to a pirated copy that was closely priced without the same guarantees of quality.

The game itself made good returns but it didn’t recoup the large investment from BreakAway. “Our partners didn’t expect this to happen because they were with us for the long-term and they had seen the opportunity of establishing a new trend in a market thirsty for Arabic gaming content,” Khasawneh adds.

Naturally, any new producer wouldn’t expect profitability from the first game they publish. Arabian Lords II would have been produced at a fraction of the original cost; this would have shot profit margins up to 90 percent of cost, according to Khasawneh and Kirk. “New big titles would have cost about $2 million and profit margins would have climbed to 80 percent instead of 40 percent. Eventually, the transfer of know-how would also happen, which lowers the cost of running the business.” Khasawneh adds. “The brand is what sells in the game design business.”

Sadly, however, Arabian Lords was to become Quirkat’s fifteen minutes of fame. The delays they faced in distribution had pushed them closer to the financial fiasco in US markets, which went into full swing late 2007. This caused their American partner to pull out too soon from the venture. Quirkat was on its own again and this time at the mercy of Arab investors who didn’t comprehend the size and potential of their niche product.

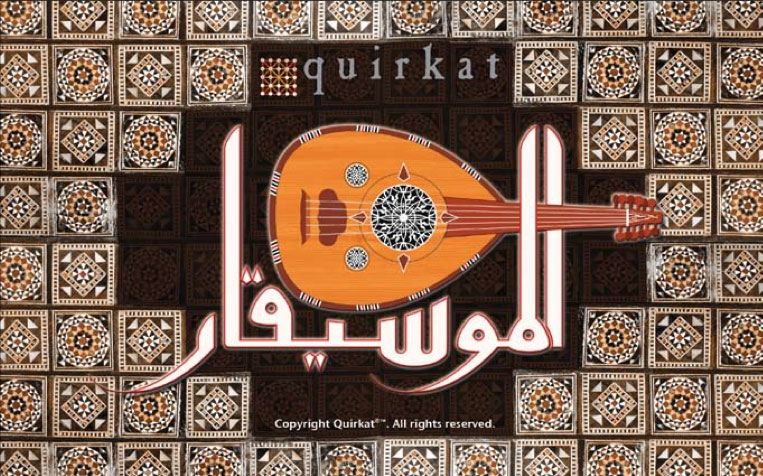

While big strategy games are for now out of reach for Quirkat, the company is still producing popular games. Their game, Al Moosiqar (The Musician), was recently named by Nokia as one of the top-10 game-downloads for the Arab region. “Al Moosiqar is an across-platform game and we’re going social with it, as in offering it on social websites like Facebook." Candide says.

Jordan, she adds, offers an advanced test-market for mobile games. “In terms of infrastructure for piloting mobile games the market helps a lot. We have here three mobile operators that give game developers the flavors of all the mobile marketing models in the Arab region,” she adds.

Globally the gaming trend is going mostly social. According to Kirk, the popular social game of Farmville has 64 million players active every month on different social websites. The game is free but when players pay a small fee they get an advantage over friends playing against them.

The size of the overall global market for electronic gaming is massive and has been growing fast along the spread and convergence of digital social interaction. The estimates for the global market is tens of billions of dollars with mobile phone gaming the fastest growing segment of the industry, according to research by US-based BCC Research. PricewaterhouseCoopers is also projecting that electronic gaming will soon overtake the ailing music industry in size.

The old world of media is giving way to the rising world of digital interactive entertainment. While in 2008 revenues from home DVD entertainment sales slid by 5.5 percent to $22.4 (Digital Entertainment Group statistics), the home gaming market in the US gained 26 percent, bringing in $11 billion. In US markets, the big game companies pay top dollars for successful game studios. Last year Electronic Arts (EA), a market leader in games, offered to buy Take-Two Interactive for $2 billion. The company rejected EA's offer as its Grand Theft Auto IV made over $500 million from sales in its first week.

“Our natural next step is to get a tech-savvy investor from the region to take the business to the next level,” says Khasawneh. This next level is $2-million investment and, according to him, it’s a perfect investment now because the games industry is recession-proof. “Studies have shown that in hard economic times game sales go up. Many people, it seems, cancel their travel plans and opt instead for spending a couple of a hundred dollars on good games,” says Kirk.

But for Quirkat the $2-million investment level they’re interested in is at once too low and too high. "Investors, we have discovered, are mostly interested in financing either a small upstart that requires around $100,000 (angel investors) or big-ticket opportunities that are over and above $10 million,” says Khasawneh.

For now, Quirkat has ruled out the strategy of relying on friends or family to raise investment capital. “Friends and family will translate to a multitude of investors on the board and that’s not a good model as the business would grow too complex to manage in terms of strategy,” says Khasawneh.

There’s obviously a great market waiting for Quirkat but without proper capitalization they won’t be able to tap it. “It’s a huge market for anyone that can play it right. Arab markets share the same language and the same sentiment, making it easier to manage and expand into. We’ve proven that this is possible with Arabian Lords and other games,” he adds.

When Quirkat joined BreakAway a “Micro Multinational” was created, says Kirk. “Such an entity allowed us to scale up and down as needed for each of our projects; we could produce the type of games that are world class and yet be able to produce smaller ones for local markets,” adds Kirk.

The partners aren’t given up on finding the right Arab investor. “We have got to make the leap with the right base to be able to introduce new original games that are mass-marketed to Arabs. If we’re well funded by the right strategic partner, we will take gaming in the region to the next level of grandiosity, with bigger productions that are IPR-protected,” adds Khasawneh.

“And if not,” Kirk continues, “we’d stay doing what we’re doing as a way to maintain our lifestyles; which is doing the best we can at high quality but at a smaller scale. Most investors still glorify anything that is imported and done by non-Arabs. This is wrong.”

Then Khasawneh adds: “It still feels as if we are living in circa 1910 in terms of investment. Change in Arab investor mentality has been too slow if one considers the pace of change elsewhere; and especially when it is concerned with technology products.”