Hate speech to dialogue: Munathara reframes online debate

Social media is often depicted as a game changer for democracy and freedom of speech, but by no means has it contributed to healthy dialogue, says Belabbes Benkredda, founder of the Arab world’s independant online debate forum Munathara.

Instead, it created more babble than ever before. Platforms like Twitter and Facebook have amplified hate speech and fake news, forcing the companies to dedicate resources to combat the issues.

In response to media platforms that favor noise over substance, Munathara instead offers the opposite. It is an online space that is open enough to include as many ideas as possible, but structured enough to keep out the trolls.

Rules of debate

Every month, the team posts a controversial statement to Munathara’s website. Participants get to either support or reject it by posting 99 second videos to present their arguments. Viewers then get to score the quality of video arguments and whether they are with or against the general statements.

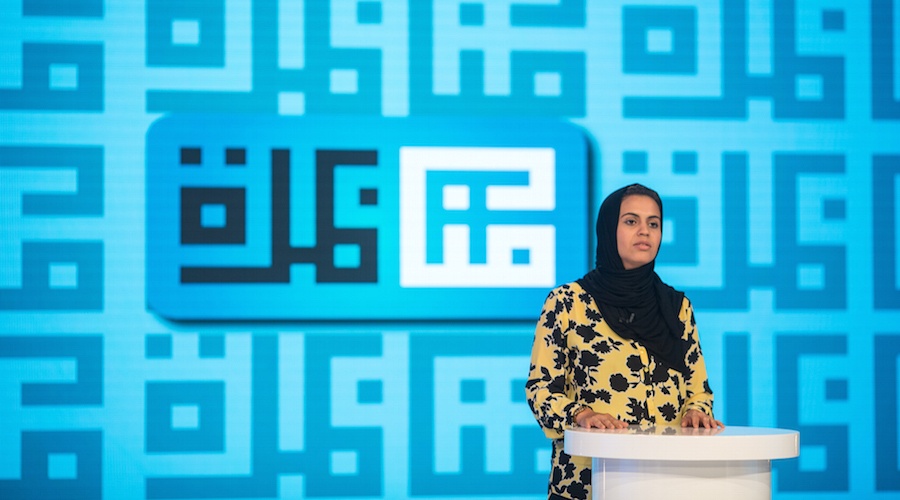

The six participants that score the highest are then given the chance to join an intensive training and take part in a televised debate with public officials.

“We never want it to be a [strictly] youth debate program because there is only so much interest in this. When we pair the youth with well-known politicians and mainstream opinion leaders, we elevate their voices further and create more interest,” said Benkredda.

Unsurprisingly, the idea for Munathara erupted at the time of the Arab Spring in 2011, when Benkredda was inspired to create a forum for the voices leading the revolution.

Nearly 25 competitions have been organized thus far on topics including politics, human rights, social justice, and religion. The platform has garnered 3,500 videos and 70,000 members.

Participation is particularly strong from Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen, and the vast majority of users are between the ages of 16 and 30.

Technology and democracy: Friends or foes?

“You can’t go to Silicon Valley and ask to fix democracy,” Benkredda said, jokingly. Social media giants like Facebook and Twitter have algorithms that are generally designed to drive business rather than encourage critical and fact-based dialogue, which is why users are more likely to see posts that align with their views on their newsfeeds than opposing ones.

Although Benkredda does not claim to have fixed the problem of online polarization, he believes Munathara’s algorithm is much more sophisticated than other social media sites. Once users have seen a video from one side of the competition, the system automatically loads a video arguing the opposite.

More importantly, the algorithm scores videos based on only two metrics. The first is endorsement level, or the degree to which a user agrees with the participant’s view. The second is performance quality, which rates oratory skill, irrespective of endorsement numbers. These metrics are tracked on a scale from 1 to 5, which adds a great deal of nuance, especially when compared to simple likes or retweets.

“Technology in and of itself doesn’t have a democratic mandate, it all depends on what we make of it,” said Benkredda. “A culture of rational and fact-based debates is either there or not. If it is there then technology can support it greatly.”