India's startup expansion to Mena: A cause for concern?

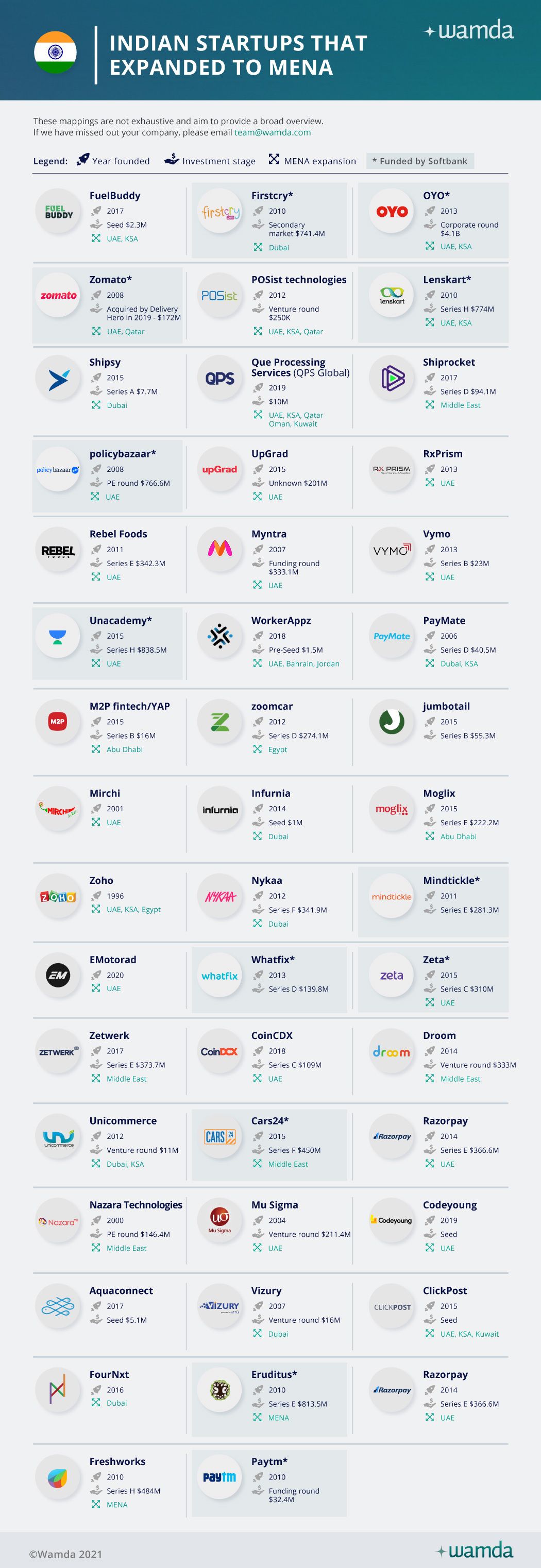

Since 2016, more than 50 India-based startups have expanded into the Middle East and North Africa (Mena) by making their UAE debut an entry point to the wider region. Twenty of these were already unicorns when they scaled and included the fintech PayMate, edtech Countingwell, and eyewear online retailer Lenskart.

Approximately, 20 per cent of the Indian startups that have established a presence in Mena are backed by the Japanese conglomerate Softbank, through its first and second $100 billion Vision Funds, while more than a quarter are funded by GCC venture firms, family offices, and angel investors.

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Investment Company, together contributed around $60 billion in the first Vision Fund, making the venture capital deployed into these Indian startups an indirect foreign investment by these sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) whose core mission is to diversify the region’s economy beyond oil.

Opening the door for more foreign startups can drive more innovation and capital to the region, but with more late-stage Indian startups coming under Vision Fund 2, and only a handful of Mena startups eyeing India, the pressure to establish relevant public policies is exacerbating.

These policies could mitigate the anxieties that hang over underfunded Mena startups, while still accommodating the entrepreneurial thirst of expanding, capital-pulling, job-creating businesses.

Big funds

VC funds in Mena continue to break records, alluring more foreign startups to set up regional offices and expand.

“Money is now a secondary factor”, says Piyush Chowhan, Lulu Group’s chief information officer, as Indian startups yearn to escape the “cutthroat” market competitiveness in India by turning to the GCC.

In 2019, 10 per cent of Indian startups’ venture rounds were led by SWFs. That same year, Qatar Investment Authority led Byju’s $150 million venture round, allowing it to expand into the UAE.

These SWF investments are typically risk-averse, says Wesley Schwalje, the chief operating officer (COO) of UAE-based Tahseen Consulting firm, and an early-stage investor in multiple Indian startups.

“I think there is hesitancy on behalf of GCC and Mena investors into looking at India in the early-stage and that's why most of the opportunities that the sovereign funds are investing in are already unicorns or ‘nearicorns’. So, there's a stronger preference for later-stage deals that have already been effectively de-risked,” he says.

Generally, two out of three seed-stage startups fail to exist or raise further funds, so early-stage startups either delay fundraising to achieve desirable traction first, or utilise local partnerships to their advantage. For expanding Indian startups, the latter is more prevalent.

"There's far more willingness to invest in early deals by members of the diaspora community. Many of the retail groups like Landmark Group and Lulu Group, and other individuals who had business experience from those family groups and conglomerates, are often times investing in early-stage deals in India where one value that they bring to the table is access to the GCC if that company wants to expand,” explains Schwalje.

Outside of lucrative communal relationships with the UAE Indian diaspora, who account for 30 per cent of the country’s population, these startups are still able to attract local angel investors in Mena who in many cases lack the practical knowledge of the Indian startup and VC space.

“GCC investors understood that we have built [our solution] for Flipkart previously and that they can rely on us. That’s the gap you’ll see with GCC investors who want to come to India but don’t know what’s happening on the ground so they look for the right kind of partner who has been there and done that,” says Rishi Rathore, co-founder and COO of Arzooo, a B2B retail tech platform.

UAE-based Jabbar Internet Group, an investor in souq.com, and Tahseen Consulting participated in Arzooo’s Angel and Series A rounds along with other leading US investors like Eric Yuan, the founder and CEO of Zoom.

With the amount of financial and communal support, Indian startups rarely start their expansion by acquiring local businesses - a strategy most international companies use to gain marketability, easy consumer recognition, and present exit opportunities for local startups.

Instead, Indian startups enjoy the backing of global investors and SWFs who support the cross-geographical tech flexibility inherent in their products, even if that is at the expense of local players.

“Our solution is a tech solution and when we talk about tech solutions it's important to understand that it comes with a lot of flexibility. The reason we have built a platform to be very flexible is because it can adapt to the local regulations and local demands. I don't need to write it from scratch when I'm going to work in Saudi or the UAE or Vietnam or Singapore. The platform is nimble enough to rule out programs very easily,” explains Vineet Saxena, co-founder of the fintech startup Card91, and the Flipkart-acquired e-commerce platform Myntra.

While flexible enough to enter a global market like the US, Card91 and other startups still choose to enter the UAE first in a much typical, and arguably strategic, move.

“The GCC, or the UAE in particular, has always been a gateway for the Indian startup ecosystem. If a startup wants to take their company global, there are two regions to enable that, Dubai or Singapore. These have always been the two regions where people have looked at in terms of setting up extension offices when they are ready for global expansion,” says Saxena.

The ease of setting up a business in the UAE is much more approachable than the US, says Chowhan, but UAE startup expansions are viewed as stepping stones for future access to the US market.

That is the case for the India-based hospitality and rental marketplace OYO Hotels & Rooms, both a Softbank and a PIF portfolio company and a recent player in the UAE and Saudi markets.

The possible downside for such well-backed unicorns entering the UAE, is the implicit pressure set upon them to complete the journey to go global.

“For any of Softbank or the wealth funds, their focus is on growth and that puts a lot of pressure on founders. For example, OYO is a really big startup in India right now and Softbank has been funding them for the past three to four years, and they've been under a lot of pressure to build numbers and grow very, very fast,” says Rathore.

OYO drove a whirlwind performance with a 50-60 per cent loss and thousands of layoffs in 2020. Softbank owns a 46 per cent stake in the startup, which is planning to file a $2.1 billion initial public offering (IPO) at the end of this year.

All of this has been pushing more Indian startups to not only enter the GCC but to set an unprecedented market growth once arriving here. For the local startup scene, the competition is only getting fiercer.

Local competition

Supported by local partnerships, startups like edtechs Cuemath and Countingwell are able to ease their integration into the Mena market in a way Mena startups themselves might find difficult.

“We started expanding [in the UAE] only a few months back and so far we tried to do that directly with D2C [direct-to-consumer], but we all realise the importance and the power of doing partnerships with institutions around here. In fact one of our investors is [Abu Dhabi’s] Alpha Wave Incubation, so we definitely see the value of these relationships and partnerships,” says Manan Khurma, the founder of Google-backed edtech startup Cuemath.

Local startups on the other hand, don’t share the same investor and immediate community support as their Indian counterparts.

“The majority of capital from our region is still being invested outside of the Middle East, and sometimes it is used to fund startups outside of the region that then come to operate here, competing with local startups,” says Anass Boumediene, the co-founder and co-CEO of eyewa, an UAE-based eyewear e-commerce platform and a Wamda portfolio company.

The lack of accessible capital, according to Boumediene, drives regional startups to turn to European, Asian or American investors for funds.

“This funding gap in the Middle East can and should be filled by our region’s large asset managers to make more capital available for the local startups and scaleups,” he advocates. “There remains some work to make the region more accessible for all, as the market is fragmented and the legal framework is different from one country to another. That remains a challenge for both local and international players.”

One-sided fear

The Mena region’s exposure to fast-growth startups can become a risky one-sided affair without relevant public competition policies, says Schwalje.

“The UAE and every other Arab state who negotiates agreements to try to build trade and investment ties needs to ensure that they’re getting as much out of it as the counterparty is,” he says. “That might be capability acquisition, local content, hiring requirements, and those can appear protectionist at first but there’s a lot of big issues in those trade developments that might appear initially short-term. The region wants to become a tech hub and bring a lot of Indian startups here, but that can have very material future implications that are hard to wrap your head around without proper policies in place.”

However, both Indian startups and local conglomerates support the influx of competition into the region believing, as Chowhan does, in the possibility to uplift the region’s talent, tech competence, and capital generation.

“That’s how you create a win-win ecosystem. If you look at it as a ‘them vs. us’ situation, then that’s not a healthy space. What happens is that capital pulls more capital, and if you create, let’s say, ten unicorns, the amount of money [that is generated] can create another hundred-million [dollar] startups. That’s how the whole ecosystem grows and I think the potential is much bigger in the UAE than what is happening today,” he says.

Allowing more startups to come in, says Chowhan, can encourage foreign firms to set regional offices, incubators, and more “startup engagement programmes” - a major element behind India’s growth.

“One of the reasons the Indian ecosystem is developed is because there are about 1200 centres for global companies in Bangalore alone and a lot more of those companies run an accelerator and/or a startup engagement programme. This brings in talent from all over the world and this global innovation concentration is able to breed new ideas because the startup ecosystem is tied to the entire startup ecosystem,” he argues.