The kid with the amazing AR glasses

Vound inventor Aly Mohamed at an EU-sponsored contest for young scientists. (Image via Wamda)

Aly Mohamed comes across as a genius.

Not at first, but as the highly advanced concepts around his augmented reality (AR) headset tumble out of him your brain gradually readjusts and starts saying, this 21-year-old kid hasn’t even been to university yet.

In 2012 Mohamed designed some goggles to aid deaf people for his school science fair.

The project escalated, first into a gap year after high school in 2013 (he was supposed to go to the UK to study economics), then a startup, and finally into a three year immersion in advanced coding and prototyping (all self-taught) and achievements such as coming third in MIT’s Arab Startup competition in 2014.

But today Vound (the merging of ‘vision’ and ‘sound’) is at a critical point: Mohamed has one more semester in a Swiss boarding school (which, after six months of shuttling between Geneva and Egypt, said he had to choose between studying for college or Vound), yet with the right attention a final product could be ready in 18 months.

Seeing sound

The Vound concept is ambitious: glasses that generate images and words from sounds, software that learns from past experiences, and artificial intelligence (AI) that flashes visual options into the glasses based on location.

Augmented reality, as opposed to virtual reality, superimposes computer-generated images over a person’s natural sight, providing an ‘augmented’ view of the world. The most infamous example is Google Glass, which Mohamed actually applied for to test-drive but was rejected because he wasn’t 21.

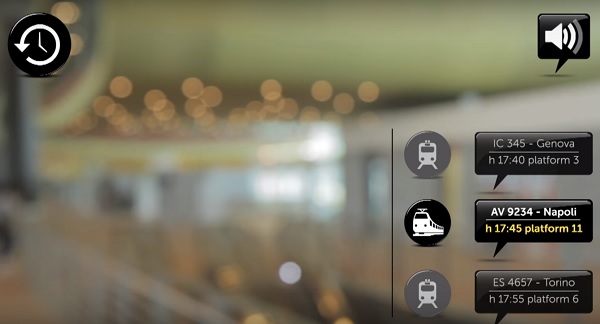

A mock-up of what Vound could look like: anthropologist Dario Pasquarella presented this app-plus-glass concept to a TEDxMilan talk, using a train station as an example location. (Image via YouTube)

Mohamed, his now-13-year-old brother and a succession of (adult) hired programmers, developed and financed the concept themselves, bar some input from a high school teacher and, more recently, some mentors in the US.

The prototype, now in its fourth iteration, was built using a bootleg 3D printer and will eventually incorporate 24 features to translate sounds into visual and physical cues.

These features include automatic voice messages to emergency services; a super-fast keyring keyboard to translate text to speech so the user won’t have to break the all-important eye-contact; AI that reads a location and flashes sentence options into headset, which it can then vocalise; voice recognition; and even the ability to convey the beauty of sounds made by wind and water - organised synesthesia, if you like.

“As a human we don’t just hear the sound, we feel it,” Mohamed said. “We’re taking the sound waves and compressing it into visual representations.”

He said the benefits were that it didn't require surgery, such as a cochlear implant, special training, and would be affordable for (most of) the 360 million people around the world with “disabling hearing loss”.

The original idea however, was not because Mohamed knew deaf people, but due to his own tunnel vision.

He’d be so focused on a task he’d not hear door bells, sirens or even people addressing him in the same room. People would assume he was deaf or even stupid, and this caused the teenager considerable stress.

But he’d been reading about a phenomena called ‘sound signatures’ so he considered the tools at his disposal: he had a virtual reality video game called Fat Shark which came with a headset, and a Raspberry Pi device.

“I really wanted to break [the game headset] to see what was inside but it was expensive, so I said I needed it for a science project,” he said, winning his reluctant parents over.

The initial outcome, however, “was really bad. I didn’t really love it.” For a start the headset was not a pair of glasses - you couldn’t see through them.

AR just got big, fast

Globally, AR and its cousin virtual reality have long been the ‘almost-there’s’ of the tech world.

"In practice, it has taken longer than just about anyone expected to get that kind of tech consumer-ready. The devil has turned out to be in the details of satisfying the amazingly finicky human visual system," Neal Stephenson wrote in 2014 when he became chief futurist at Magic Leap.

And from Epic Games' CEO Tim Sweeney during last year’s ChinaJoy trade show: “I believe that augmented reality will be the biggest technological revolution that happens in our lifetime.”

Their arrival has been prophesied for years and in the last few months the market for both has just begun to fire.

Oculus Rift plans to launch in March and Samsung’s Gear VR, which went on sale last year, is being labelled as the device that’s made virtual reality for the masses a “thing”. Google is also developing a headset for smart phones, building on the Cardboard concept, to be released this year too.

Startup data-monger CB Insights reported in January that investment in virtual and augmented reality startups hit an “all time high” in the fourth quarter of 2015, as investors sank $658 million into 126 deals.

To give an idea of just how nascent this sector is, three quarters of those deals were in early stage businesses.

Industry consultant Digi-Capital (whose total AR/VR investment counter hit $686 million for last year) said that money was being put into video, services, games and head-mounted displays.

“This year could be the tipping point for AR/VR investment moving from a few intrepid investors to the broader VC and corporate investor community. The next platform shift to AR/VR looks like it could drive growth to $120 billion by 2020,” the company said in a blog post in January.

AR is as new for entrepreneurs in MENA as in the rest of the world, but as reported by Wamda in August last year, there are a growing number of regional startups in this space, based mostly in the UAE or, now, the US.

Pixelbug and TakeLeap are AR content providers, enterprise-oriented glasses developed by Atheer Labs (founded by Lebanese entrepreneur Soulaiman Itani but based in Palo Alto) went on sale in January, and medical applications for the technology are being developed and tested in the region.

Will Vound come too late?

In Wamda’s fishbowl-like interview room Mohamed, apologising repeatedly for not being “good one on one”, rapidly flicked through slides showing the public - as well as the highly confidential - workings of the Vound headset.

With money borrowed from his dad, he’s applied for three patents in the US, but is very nervous about the future of his passion project.

The only college he’s applied to is MIT, which has a 3 percent acceptance rate, because it’s the only one he feels has the support he needs to make Vound a success. And he’s close to reaching the age limit of 22 for his other option, the Thiel Fellowship, a $100,000 scholarship for kids who want to drop out and build an idea rather than sit in a classroom.

There’s a risk that if he waits longer, someone else will commercialize his product first.

The broad concept was well established before Mohamed thought of it. The beautifully designed BabelFisk was released in late 2010, although only as a concept. In 2012 anthropologist Dario Pasquarella presented an app and specialised glasses at TEDxMilan that performed almost - not quite, but almost - exactly as Vound is intended to. Meta launched the first commercial AR glasses system in 2014, and a multitude of others were available to buy or order by the end of last year.

Speech recognition software is also rapidly improving, from open source applications such as Pocketsphinx or paid-for options, and the entry point for adapting high-level AI and machine learning technology in devices is dropping.

In MENA the competition is focused on sign language translation, as KinTrans launches its enterprise-oriented translator in the UAE and Lebanese startup Mimix's app is already in the market, in the Google Play store.

As the AR market heats up more designers and entrepreneurs will inevitably realise the same potential in the deaf market for 'visual hearing aids' as Mohamed did in 2012.

Yet with the final version of a self-designed, technologically advanced product potentially only 18 months away, and older prototypes receiving good feedback from San Francisco's deaf community and experts at MIT and Harvard, the world would appear to be the 21 year old inventor’s oyster - if he can get there first.